November 5, 2025

“There is no royal flower strewn path to success. And if there is, I have not found it, for whatever success I have attained has been the result of much hard work and many sleepless nights.”

In Philadelphia, in 1917, two hundred cooks, laundresses, teachers, mothers, and others packed the Union Baptist Church for CJ’s first national sales convention. They watched as she handed out prizes for sales achievements and community work. Her messages didn’t stop with business. She urged them to organize and vote. She stressed, “I want my agents to feel that their first duty is to humanity.” By then, CJ’s company said it had trained close to 20,000 women. *Harvard Business Review* frames the operation as a system to use business for economic mobility. The operating logic was simple: build skill, build status, build income — more about my journey.

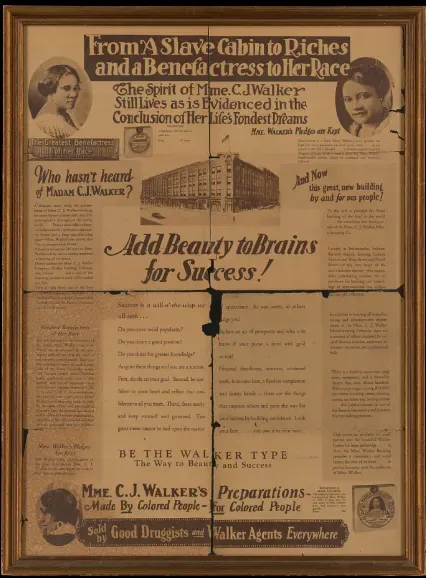

People know the headline about Madam C. J. Walker. She was the first female self-made millionaire. On the surface, it looks like she made her fortune selling a hair care product in a jar. But the jar actually served as a way for her to build a training and distribution engine. That’s what earned her millionaire status.

Her most important impact, though, came from the lives her business changed. Her business turned tens of thousands of low-wage workers into skilled moneymakers. This wasn’t door-to-door churn. This was a trade of standards, coursework, and advancement.

Hair care in the early 1900s had a blind spot. Products ignored textured hair and the scalp damage caused by hard water and harsh soaps. Walker recognized the gap in the market and stepped in to fill it with a tiered plan: formula, method, and training. A century later, the sheer size of hair care in general, and the black sector in particular, suggests maybe even she underestimated the opportunity.

In 2024, the hair care industry had a market size of $107 billion and is forecast to reach $213 billion by 2032. The African American hair sector alone cleared $10 billion in 2023, tracking for $15 billion by 2033. Walker operated in another era, one with smaller revenue numbers and less sophistication, but her model reads like a modern playbook: develop a solid method, teach it to a driven group, standardize service, and route distribution through trusted hands.

“I am not ashamed of my past; I am not ashamed of my humble beginnings.”

CJ was born Sarah Breedlove in 1867 near Delta, Louisiana. Sadly, she was an orphan by age seven, and her parents both passed within a year of each other. She lived with her sister- and brother-in-law, but It wasn’t pleasant. Every morning she woke up and worked cotton fields, only to suffer abuse at the hands of her brother-in-law when she returned. She married Moses McWilliams at 14 in an effort to escape.

The two had a baby, but Moses died six years into their marriage. It left CJ as a single mother and looking for a way out of poverty. She moved to St. Louis, where her brothers worked as barbers. She became a laundress and cook and, through her church, met educated men and women. Their success inspired her to pursue success of her own, and she had another brief marriage. It didn’t work out, and she continued to suffer financially.

The hardship and years of physical labor led CJ to deal with hair loss. She began using Annie Turbo Malone’s “The Great Wonderful Hair Grower” in 1904. A year later, she joined Annie’s business as a sales agent from 1905 to 1906. Annie deserves full credit for building her own powerhouse with Poro College and a formal school built around her products. It also sparked a massive debate pertaining to CJ’s life.

“I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations.”

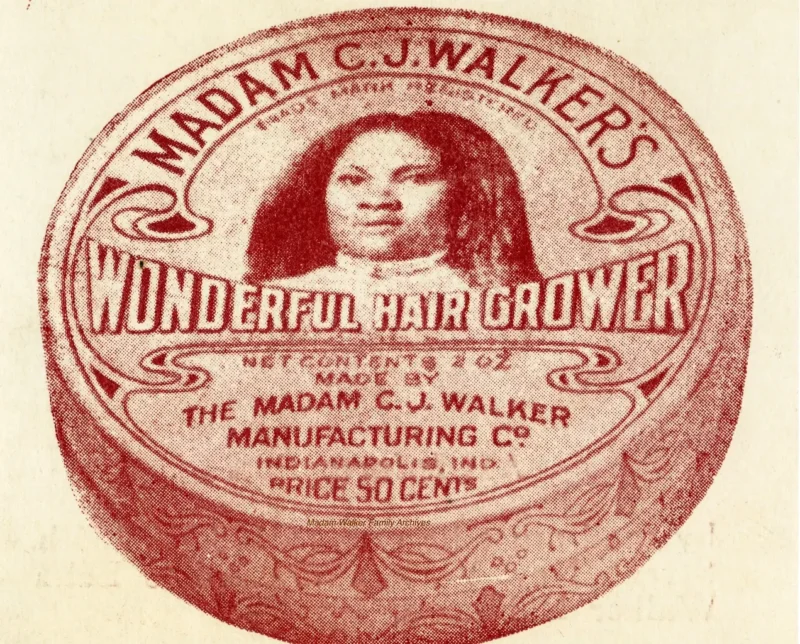

CJ moved to Denver, married Charles Joseph Walker, and took on the name Madam CJ Walker. Then, her life took a dramatic change. In 1906, with $1.25 (less than $50 today), she created the products that she ultimately turned into an empire. She focused on hair straighteners and growers specifically for African American women, naming her product “Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower.”

Hence the debate. The overlap between CJ and Annie led to a rivalry in the community. Many felt that CJ stole the formula and business model. A’Lelia Bundles, Walker’s biographer and great-great-granddaughter, wrestles with the debate. She acknowledges the connection to Annie, but also points out CJ’s brothers worked as barbers and introduced her to hair care. Taking a step back, she highlights that sulfur-based ointments designed to soothe and heal scalp infections dated back to the 1700s, nearly 200 years before either product.

“I got my start by giving myself a start.”

CJ definitely took a page out of Annie’s playbook, but she executed it differently (and more effectively). Annie concentrated power at Poro College, a flagship campus with classrooms, dorms, and an auditorium that projected authority, but it tethered scale to St. Louis.

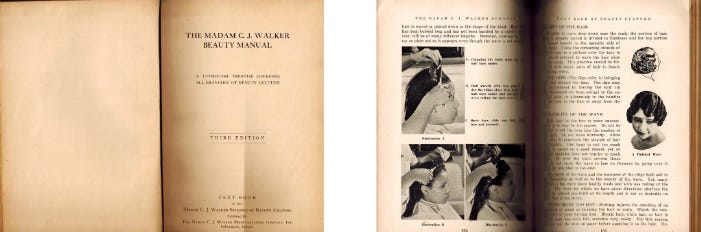

Walker optimized for surface area. She distributed correspondence courses across the country, executed traveling demonstrations, established local schools in various cities, and published a standardized textbook so any serious agent could plug in fast.

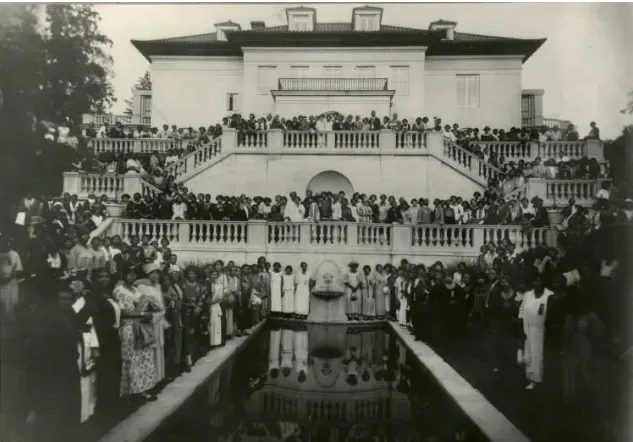

She also focused on building a community, not just an organization for jobs. Her 1917 agents’ convention formalized recognition and tied advancement to community service as well as sales. That structure turned customers into community nodes and multiplied distribution well beyond a single hub.

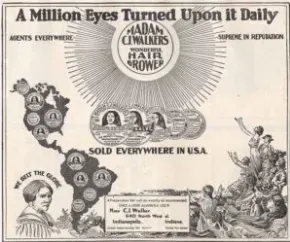

Finally, she advertised relentlessly in the Black press, recruited through church and club networks, and used her public platform, including Villa Lewaro, to signal status to prospects and buyers.

The title “Madam” functioned as a portable brand standard, and the Walker System standardized service from city to city. She built a brand plus operating system that scaled across the U.S., the Caribbean, and Central America without losing coherence.

“Don’t sit down and wait for the opportunities to come. Get up and make them.”

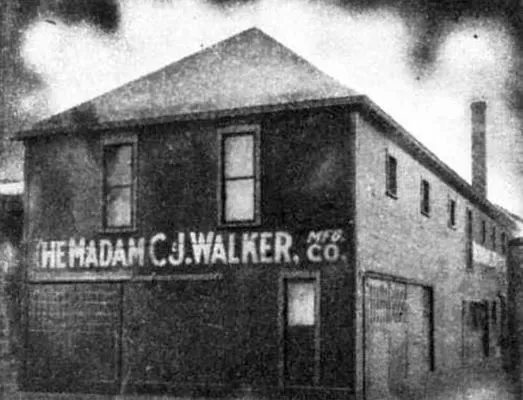

After launching her venture in Denver, CJ moved the business to Indianapolis in 1910. She recognized Indianapolis as a strategic location for expansion. Indianapolis was a growing industrial and transportation hub with a sizable African American population supportive of Black-owned businesses. The move allowed Walker to establish headquarters with a factory, salon, and beauty school all under one roof, creating a vertically integrated operation.

Walker solved a precise problem: damaged scalps and fragile hair in a world of lye soaps and hard water. Sulfur treatments, botanical oils, and strict hygiene aimed at restoring scalp health and encouraging growth. The pitch blended practical science with trusted remedies and set the tone for a century of textured-hair innovation. CJ’s method of hair care stressed using her product alongside frequent washing, scalp massage, and controlled heat. The pressing comb (a heated hair tool usually used for straightening hair) mattered, but hygiene and habit did most of the work. None of it mattered without incredible storytelling. She told everyone the formula came to her in a dream. The combination fit a market that lacked safe options and trusted guidance.

This centralization helped formalize training for agents, ramp up production, and build community outreach within a supportive urban environment, accelerating her company’s scale and influence. The Indianapolis base became the heart of the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company and remained so throughout her career.

She kept the brand tight. The same portrait on every tin. The same copy lines. The same steps. Ads ran where her buyers read, into living rooms and parlors. Ads promised dignity and self-reliance as much as shine.

She trademarked the items and updated the manuals as the line expanded.

It quickly became clear she sold more than ointments for haircare when copycats showed up, offering similar products to hers. She answered by elevating the business to be more than the product. Ceremonies, certificates, and consistent training turned quality control into part of the brand, the method, and certifying her agents. The schools taught technique and financial literacy, which kept a door open to improve the tools of the trade.

“I have made it possible for many colored women to abandon the washtub for a more pleasant and profitable occupation.”

The real product was upward mobility and opportunity. Agents paid for training and learned product science, sanitation, demos, and bookkeeping. Not everyone who wanted to take the training could travel, so CJ offered the courses by mail. Think of them as the online courses of the early 20th century. Company and contemporary accounts place the network near 20,000 trained agents by 1917–1919.

The workday had a beat. Church visits. Home demos. Wash, massage, talk, press. Book next appointments. Track reorders. Handle objections. Agents sold solutions first, product second, and relationships always. The company reinforced the craft with a textbook that covered biology, sanitation, disease, and business practice. You can read it cover to cover today. It is a century-old playbook for service-led sales.

If you’ve sat through a home party or watched a cousin pitch skincare on social media, this will sound familiar. Walker’s engine ran on direct selling: person-to-person demos, social trust, bookings, and reorders. The idea of connecting community with demos became popular and more ubiquitous in the 1930s when Frank Beveridge recruited housewives to host parties where he could demonstrate household appliances to a group instead of traipsing door to door. Then, Brownie Wise cut the men out of the equation with Tupperware parties in the 1940s, providing women with opportunities to grow businesses.

CJ beat Brownie to the party by over 20 years. Her platform had strong economics, and agents earned more working for her than they could by doing domestic work. They earned $15 to $40 a week, giving them a path out of subsistence and into savings and status. Agents became central in their community. Many worked from home parlors or small storefronts that doubled as hubs of local information.

Walker put structure around the network. In 1916 she formed the National Beauty Culturists and Benevolent Association of Madam C. J. Walker Agents, a dues-paying body with real benefits and rules. Members paid 25 cents a month. The dues funded a $50 death benefit for agents’ families (about $1,500 today), a community-based precursor to life insurance.

The association pushed local unions to do philanthropic and educational work and awarded prizes for it. They held regular regional and national meetings so agents could swap tactics, standardize service, and get recognized in public. Within a year they were on a national stage in Philadelphia, adopting resolutions and sending them to President Wilson. Historians call the 1917 meeting one of the earliest national gatherings of women entrepreneurs focused on commerce.

In their 1917 convention, the participants adopted resolutions aimed at civic leaders. CJ pushed her agents to vote, organize, and show up. The 1917 Silent Parade against lynching in New York is another example of the activism she and her agents participated in. Archival references place Walker among the signers and supporters of that moment. CJ made developed culture by making it policy.

The structure evolved. The group changed its name to the Madam C. J. Walker Hair Culturists Union of America and kept convening through the early 1920s. The combination of her products, training, certification, and community-building made her incredibly successful.

Was she the first self-made female millionaire in the United States? Guinness says yes, and period papers called her a millionaire while she lived. Historians add nuance because other records aren’t conclusive. Company receipts grew fast in the 1910s, with modern summaries putting peak-year revenues in the mid–six figures, or several million in today’s dollars.

Share Value Beyond the Spreadsheet

In 1918 she finished Villa Lewaro in Irvington, New York, designed by Vertner Tandy, the first Black registered architect in the state. Thirty-four rooms. About 20,000 square feet. It became a gathering place for artists and activists and later a National Historic Landmark. The designation files and preservation records hold the details.

The house signaled intent. It set a Black woman entrepreneur alongside the estates of America’s old-money titans. In 2018, the New Voices Foundation acquired the property with plans to use it in support of women of color entrepreneurs, a modern echo of its original purpose.

“I want you to understand that your first duty is to humanity. I want others to look at us and see that we care not just about ourselves but about others.”

She treated money like a lever. She funded YMCAs, paid tuition at Tuskegee, and pushed anti-lynching efforts. In 1917, she joined Harlem leaders to petition the White House after the East St. Louis massacre. Just before she died in 1919, she sent $5,000 to the NAACP for anti-lynching work and left two-thirds of future company profits to charity.

“There is no royal flower strewn path to success. And if there is, I have not found it, for whatever success I have attained has been the result of much hard work and many sleepless nights.”

You might also enjoy: Josephine Cochrane.

Walker gives us so many important lessons today. Of course, it’s inspiring how she came from such a rough childhood to become a self-made millionaire (in the 1920s!). But she’s more than inspirational, she’s instructive. She didn’t rely on selling a product to become successful. She used the product to build a system, brand, community, and standardized (thus scalable) business. By creating an organization that delivered high-paying jobs, pride in community, and high standards, CJ created a playbook that has survived over one hundred years. Her tactics and strategies still work today. She’s amazing.

Shaun Gordon scaled a company to 1,000 employees, built and sold two businesses, and now acquires companies through Astria Elevate in Dallas. Whether you’re building, buying, or thinking about what’s next — he’s always happy to talk.