Josephine Cochrane’s story isn’t just about inventing a machine—it’s about overcoming obstacles, breaking barriers, and leaving a legacy we rely on daily.

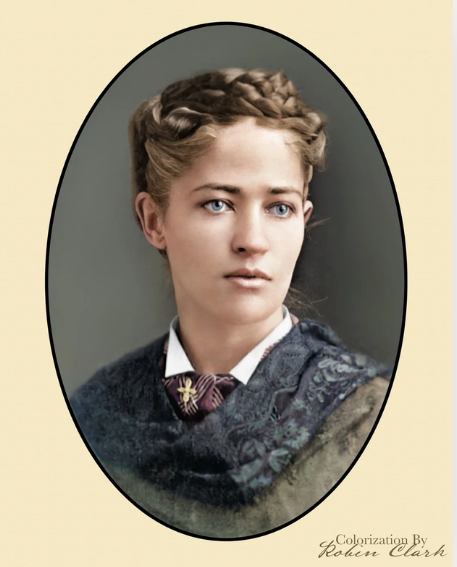

Josephine Garis grew up in a time when women’s lives revolved around domestic responsibilities. She had ambitions beyond the traditional social roles of the late 1800s, but it took her a while to realize them.

She married William Cochrane in 1858 and moved into a life of hosting elegant gatherings at their Illinois mansion, where they served their guests on china made in the 1600s.

She became frustrated when her servants chipped the heirloom tableware while they washed it. We might not think of handwashing as hard on dishes, but Josephine wasn’t the only one dealing with chipped china. It was actually a common occurrence.

On top of the damage to her precious dishes, it took so much time to wash them all. Josephine imagined a machine that could safely wash her china. She got so frustrated, she exclaimed, “If nobody else is going to invent a dishwashing machine, I’ll do it myself.”

Reality forced the dream forward.

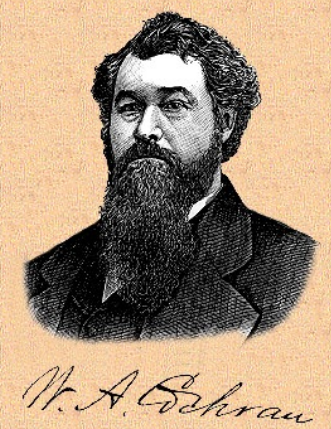

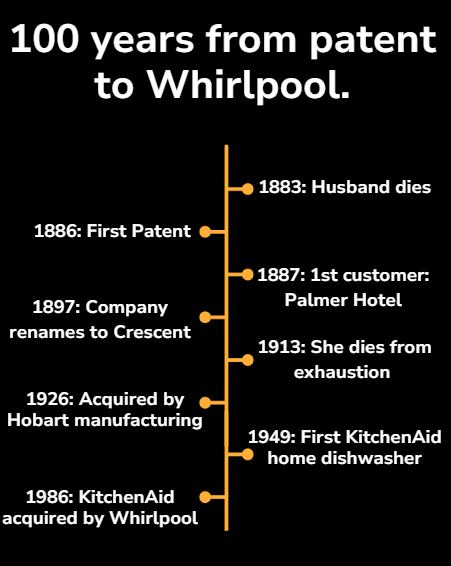

And in 1883, when her husband died, the dishwasher became more than an imaginary luxury for Josephine. Her husband liked to gamble. He also liked to drink. He left Josephine with a pile of debt and only $1,500 in savings. That’s just $47,000 in today’s dollars.

Left financially strained by the debts she hadn’t known about, Josephine needed to support herself and started developing the dishwasher. She saw clearly now: inventing became her lifeline.

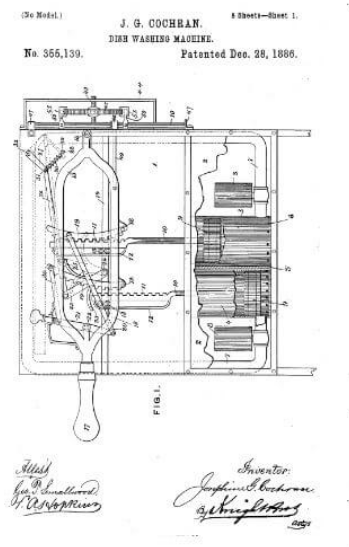

With no formal engineering education, she sketched out her initial ideas by hand. She designed a machine that securely held 200 dishes at a time in wire compartments and shot water at just the right pressure to clean them safely. Oh, and a cycle took two minutes, not two hours like it does today. The initial concept came easily; turning it into reality proved far more challenging.

Men dominated manufacturing, patents, and machinery, often dismissing women entirely in the late 1800s. Adding to the struggle, Josephine lacked formal mechanical training and only had a high-school education. Undeterred, she sought out help and found it in George Butters, a mechanic. The two of them translated her sketches into metal and wood prototypes. Josephine learned the language of machines, from gears to pulleys to water pressure dynamics, and her dream of a dishwasher started to take shape.

On the world stage

After refining her design, Josephine filed a patent for the dishwasher on December 28, 1886 (U.S. Patent No. 355,139), and the patent office awarded it to her. She claimed a crucial victory with the patent, and then she got another big win.

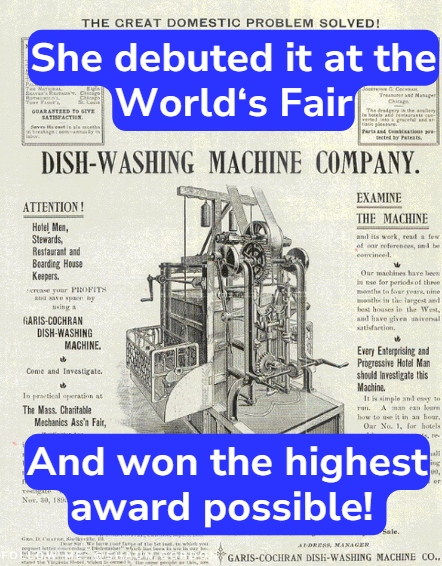

Josephine debuted the design at the World’s Fair in Chicago, 1893. She gambled everything on the Exposition, where she personally demonstrated her invention, tirelessly loading dishes into the racks, activating the jets, and impressing crowds with clean, intact china.

The dishwasher earned the Exposition’s highest prize for “best mechanical construction, durability, and adaptation to its line of work.” Despite the patent and the highest honor, she didn’t get a flood of sales. She also struggled to raise capital. Nobody saw her, a woman, as capable of building a company. In 1889 the Women’s Journal wrote, “Mrs. Cochrane is trying to get some one to form a company for the manufacture of her invention, as she is not able to establish this herself.”

The market put up plenty of obstacles for her. Josephine wanted to sell them directly to women. She understood their struggle of managing the household chores. The problem? She faced a few. The first was price, as $75-$100, was steep for most households. The second was practical. Many houses did not have the hot water necessary to run the machine. Finally, society did not equate time as money like we do now, and the wife didn’t make money decisions back then.

This quote from the Chicago Record-Herald in 1912 sums it up, “When it comes to buying something for the kitchen that costs $75 or $100, a woman…has not learned to think of her time and comfort as worth money.”

Finding a new fishing hole

With households not proving to be the viable market she imagined, she looked for customers elsewhere. She looked for corporate buyers in hotels. They had the plumbing for the machine, and needed a solution to wash a high volume of dishes. To get a sale, though, Josephine had to overcome cultural stigma.

“You cannot imagine what it was like in those days…for a woman to cross a hotel lobby alone. I had never been anywhere without my husband or father—the lobby seemed a mile wide. I thought I should faint at every step, but I didn’t—and I got an $800 order as my reward.” -Josephine Cochrane

The Palmer Hotel in Chicago became her first customer, a hard fought victory (and one long in the making). The second order, from the Sherman Hotel, came quicker. With two prestigious clients, she got social proof, and sales picked up.

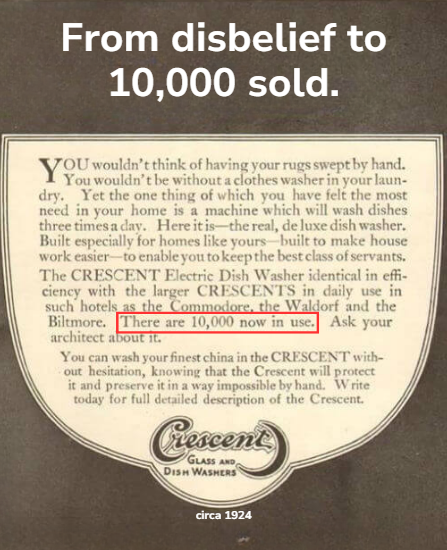

From disbelief to 10,000 sold

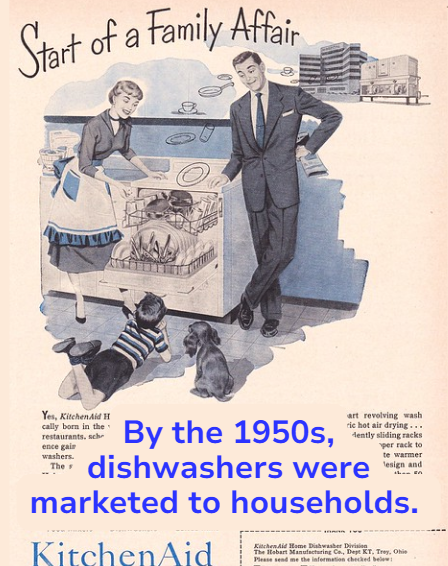

It took decades before her invention finally made it into the home, where she imagined it belonged. The wealthiest families ordered first, but by the 1950s, the machine got marketed to regular households.

The headwinds she faced before flipped. More houses got hot water. The price of the dishwasher dropped, so more people could afford them. The post-war economic boom put more money in the average budget as well.

Josephine did not live to see her invention make it there. She died in 1913 from “nervous exhaustion.” We would call it a stroke today. Ultimately, she was a woman CEO in a man’s world and felt the pressure to push herself to succeed until her body gave out at 74.

Sneaky impact

Yes, the dishwasher changed household cleaning forever, and her company lives on in a way. In 1926 Hobart Manufacturing acquired the company. It ultimately became a company you certainly know: KitchenAid.

But Josephine’s dishwasher had bigger benefits for the world than faster dishes. It changed kitchens everywhere, both domestic and commercial, by making them more efficient, but it also dramatically improved sanitation. Fewer diseases spread.

We also cannot discount how she changed expectations about women’s capabilities in innovation and entrepreneurship. Josephine’s perseverance, courage, and clarity of vision redefined what’s possible, even against formidable odds.

Her life swung from privilege to desperation to gritty determination, and it’s a lesson to the people building the inventions our grandchildren will take for granted. Answer the call, overcome the trials you’ll face, savor the victories, and transform the world.

When you need inspiration, pause and think of Josephine Cochrane, the determined woman who decided, “I’ll do it myself,” and changed the world.